Situational Awareness Training Guide

Quick Answer

In 1995, Dr. Daniel Simons conducted an experiment at Harvard that would fundamentally change how psychologists understood human attention. He asked subjects to watch a video of people passing basketballs and count the passes. Midway through the video, someone in a gorilla suit walked into the frame, stopped, beat their chest, and walked off. Fifty percent of viewers never saw the gorilla. They weren’t lying or distracted—their brains literally didn’t process the information. Simons had demonstrated what he called “inattentional blindness,” the phenomenon where focused attention on one task renders you functionally blind to unexpected events, even obvious ones. This matters profoundly for personal safety because research from institutions like Hofstra University and the National Crime Victimization Survey reveals that criminals exploit this blindness systematically—they select victims who display inattentional patterns. But here’s what the research also shows: attention is trainable. Studies demonstrate measurable improvements in threat detection within 6-8 weeks of structured practice. Situational awareness isn’t a mystical sixth sense possessed by Special Forces operators—it’s a cognitive skill built through specific exercises that reshape how your brain allocates attention. This guide presents the training methodology backed by decades of research in cognitive psychology, military science, and criminal behavior analysis.

Table of Contents

- The Invisible Gorilla Problem

- The Three-Level Model of Awareness

- Why Cooper’s Color Codes Actually Work

- Level One: Training Your Brain to Perceive

- Level Two: From Seeing to Understanding

- Level Three: Predicting What Happens Next

- The Smartphone Problem

- What Success Actually Looks Like

- Why Awareness Skills Degrade

- Building Your Training System

The Invisible Gorilla Problem

Simons’s gorilla experiment became famous, spawned a bestselling book, and generally made everyone feel bad about their attention spans. But the more interesting discovery came from his follow-up studies. When he repeated the experiment with subjects who’d been warned about the gorilla, they saw it—but then missed other unexpected events he’d added to the video. A curtain changing color. A player leaving the game entirely. Your attention, Simons demonstrated, works like a spotlight with a limited beam. You can aim it where you want, but everything outside that beam exists in functional darkness.

This explains something that’s puzzled crime researchers for decades. Dr. Betty Grayson at Hofstra University filmed people walking down New York City streets, then showed the footage to convicted violent offenders in prison. The criminals consistently identified the same individuals as easy targets. What were they seeing? Physical vulnerability? Expensive belongings? Gender differences?

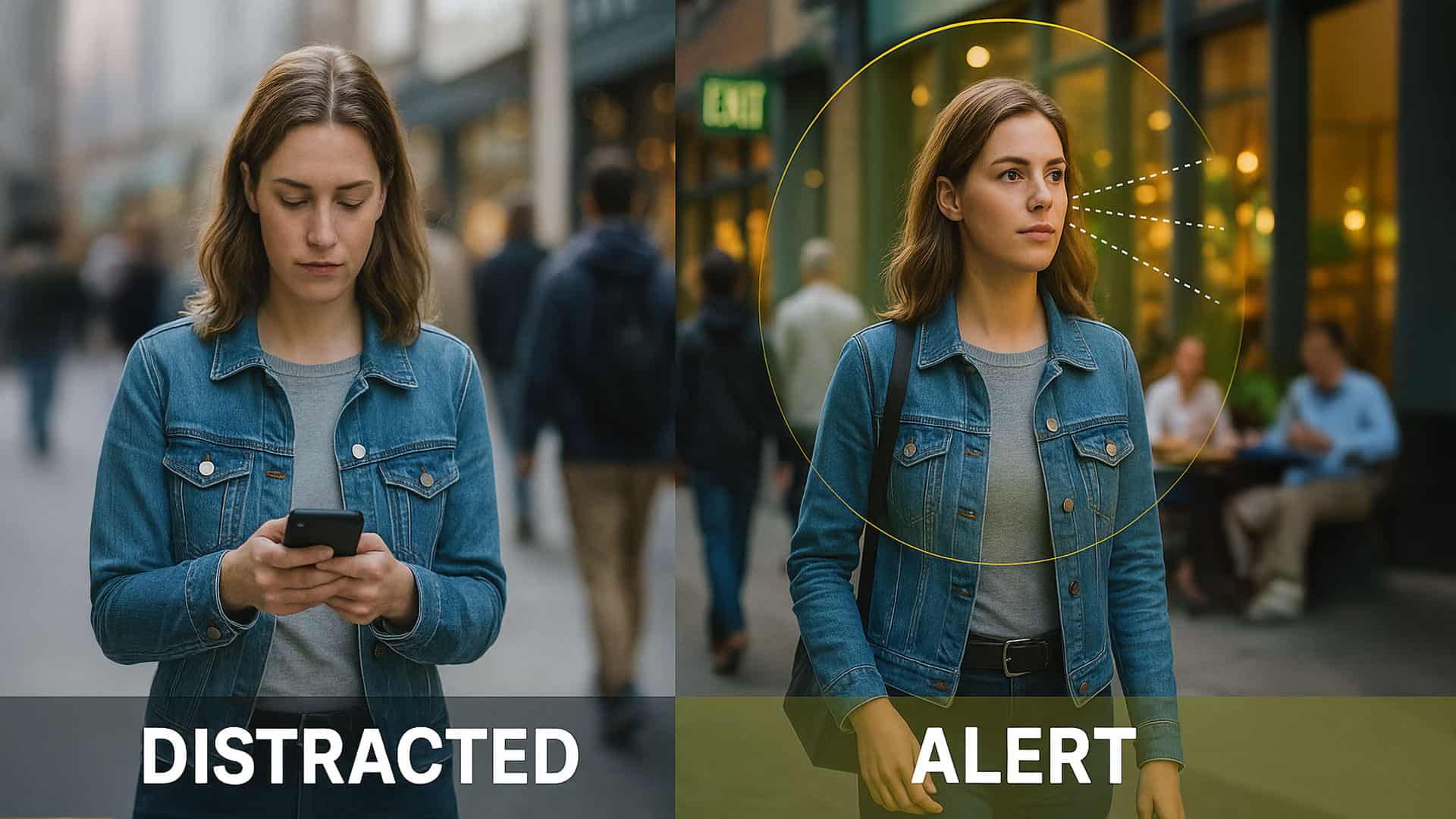

None of those factors predicted target selection with any consistency. What predicted it was something Grayson called “gait signatures”—subtle patterns in how people moved and, crucially, where they directed their attention. People whose attention spotlight was aimed inward—at their phones, their thoughts, their immediate task—moved with what Grayson described as disrupted wholeness. Their stride length was inconsistent. Their arm swing was constrained. Their head position was fixed rather than scanning.

The criminals weren’t responding to weakness. They were responding to inattentional blindness. A victim displaying these patterns wouldn’t see the approach. Wouldn’t recognize the threat. Wouldn’t have time to respond. The attack would be over before their attention spotlight swung around to register what was happening.

But here’s what Grayson discovered that matters more: she brought subjects back for training in environmental scanning and filmed them again walking the same streets. Their gait signatures changed. Not because they looked more aggressive or intimidating, but because their attention patterns changed. And when she showed the new footage to different incarcerated offenders, those same subjects were no longer identified as easy targets.

The implication is profound. The difference between people who get targeted and people who don’t isn’t about size, strength, or martial arts training. It’s about where they aim their attention spotlight. And unlike size or strength, that’s completely trainable.

The Three-Level Model of Awareness

Dr. Mica Endsley spent two decades studying how air traffic controllers, pilots, and emergency room physicians maintain awareness in high-stakes environments. She developed what’s become the standard model for understanding situational awareness—not as a single skill but as three distinct levels that build on each other.

Level One is perception—the raw data your senses collect about your environment. How many people are present. Where the exits are located. What sounds you’re hearing. The lighting conditions. Someone operating at only Level One is collecting information but not processing it. They’re the person who can tell you five people entered the coffee shop but couldn’t describe any of them or explain what they were doing.

Level Two is comprehension—understanding what the perceived information means. This person doesn’t just notice five people entered; they register that four were couples or groups who headed immediately to tables, while one entered alone, didn’t approach the counter, and is now standing near the bathroom hallway scanning the room. Level Two is about pattern recognition and context. Is this behavior normal for this environment? Does it fit the baseline, or does it break it?

Level Three is projection—predicting what happens next based on current patterns. The person standing near the bathroom hasn’t made eye contact with anyone, keeps his hands in his pockets, and keeps glancing at the register and the front door. Based on these patterns, Level Three awareness predicts: this person is either waiting for someone (and should make contact or check their phone within the next 60 seconds), is lost or confused (and should approach someone to ask questions), or is conducting pre-robbery surveillance. If the predicted normal behaviors don’t occur, threat probability increases.

Endsley’s research with aviation experts revealed something unexpected: experts don’t consciously work through these three levels sequentially. Through extensive experience, they’ve collapsed the process into what looks like intuition but is actually automated pattern matching. The expert pilot glances at instruments and knows immediately that the current configuration predicts an engine failure in three minutes. They’re not calculating—they’re recognizing a pattern they’ve seen hundreds of times in training.

This matters because it suggests situational awareness isn’t about becoming more vigilant or more paranoid. It’s about building a library of patterns so your brain can run recognition algorithms automatically. The conscious, effortful part is the training. The operational part—the awareness you use in daily life—runs in the background, throwing alerts when patterns break.

Research from the U.S. Army Research Institute supports this model. They studied soldiers at different experience levels and found that novices got overwhelmed trying to notice everything. Intermediate soldiers performed better by focusing consciously on specific elements. But elite soldiers appeared to notice things effortlessly—not because they had better senses or attention spans, but because they’d trained pattern libraries so extensively that recognition became automatic.

The training implication is clear: you can’t develop Level Three projection without first building Level One perception and Level Two comprehension. And you can’t build comprehensive pattern libraries overnight. The research suggests 6-8 weeks of structured practice to establish basic competence, with ongoing maintenance to prevent skill degradation.

Why Cooper’s Color Codes Actually Work

In 1975, Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Cooper created what he called the “color codes of awareness”—a simple framework that’s been taught in self-defense classes ever since and generally dismissed by researchers as common sense dressed in military terminology. But recent work in cognitive psychology suggests Cooper was onto something more fundamental about how human attention functions.

Cooper’s system has four states: Condition White is complete inattention—absorbed in your phone, lost in thought, no environmental scanning. Condition Yellow is relaxed alertness—aware of your surroundings, casually scanning, processing the environment but not focused on specific threats. Condition Orange is focused attention on a specific potential threat—someone approaching in an unusual way, an argument escalating, a situation developing. Condition Red is threat confirmed and immediate response initiated.

What makes this interesting from a research perspective is how it maps onto what neuroscientists understand about attentional states. Dr. Michael Posner at the University of Oregon, who spent decades mapping the brain’s attention networks, identified three distinct systems: alerting (maintaining readiness to respond), orienting (directing attention to specific locations or stimuli), and executive control (managing conflicts and making decisions).

Condition White represents minimal activation of all three networks—your alerting network isn’t maintaining readiness, your orienting network isn’t scanning for stimuli, your executive control network is focused on internal thoughts or tasks rather than environmental management. This is fine when you’re genuinely safe—home with locked doors, familiar secure environments. But maintained in public spaces, it creates what researchers call recognition latency. By the time your brain shifts from White to awareness that a threat exists, the threat has already closed distance, established advantage, or limited your options.

Condition Yellow activates the alerting and orienting networks while keeping executive control available but not engaged. Research shows this state consumes remarkably little cognitive energy—subjects can maintain it for hours without fatigue because it doesn’t require focused concentration. It’s the mental state you’re in when driving familiar routes, where you’re processing traffic and road conditions continuously but not thinking about it consciously.

Condition Orange engages all three networks—you’re maintaining high alertness, you’ve oriented toward a specific stimulus, and your executive control is actively evaluating and planning. This state is metabolically expensive. Studies show people can only maintain this level of focused attention for 15-20 minutes before performance degrades significantly.

What Cooper understood intuitively, and what research has confirmed, is that the goal isn’t maintaining maximum vigilance constantly. That’s exhausting and ultimately counterproductive. The goal is maintaining Yellow as your default public state—enough activation to catch pattern breaks quickly, but not so much that you burn out your attention systems.

The training challenge becomes: how do you make Yellow automatic? Research from habit formation studies suggests it takes approximately 50-70 repetitions of a behavior before it begins to feel automatic. This matches what military and law enforcement training has found empirically—recruits need 6-8 weeks of consistent practice before Condition Yellow becomes their default state rather than something they have to remember to do.

Level One: Training Your Brain to Perceive

In the 1960s, Soviet psychologist Alexander Luria studied chess grandmasters and discovered something unexpected about expertise. When shown a chess position from an actual game for just five seconds, grandmasters could recreate the entire board position from memory with near-perfect accuracy. But when shown a board with pieces placed randomly—not following legal chess moves—their recall dropped to average levels. They weren’t memorizing piece locations. They were recognizing meaningful patterns.

This finding has been replicated across dozens of domains. Expert radiologists detect tumors in X-rays that novices miss, not because they have better vision, but because they’ve trained pattern recognition for thousands of hours. Expert pilots recognize instrument configurations that predict problems. Expert mechanics hear engine sounds that signal specific failures.

The implication for situational awareness: you can’t comprehend what you haven’t first perceived, and you can’t perceive what you haven’t trained your brain to recognize as meaningful. The first training phase builds basic perception through exercises that force your attention spotlight to scan systematically rather than randomly.

Exercise One: The Five-Second Environmental Scan

Research from cognitive psychology shows that habits form through consistent cueing and repetition. The five-second scan uses a timer as the cue: set your phone to vibrate every five minutes. When it buzzes, stop what you’re doing and conduct a five-second scan—sweep your attention through your immediate environment in a systematic pattern. Front, left, right, behind, exits, unusual elements.

Dr. Wendy Wood at USC, who studies habit formation, emphasizes that new habits must initially be practiced in consistent contexts. Start with low-pressure environments—your home, familiar coffee shops, libraries. Practice for 30 minutes daily for three days. Then move to public spaces with more stimuli—grocery stores, shopping malls. After seven days, practice continuously whenever you’re in public.

The goal isn’t maintaining conscious vigilance. The goal is training your brain’s alerting network to activate automatically in public contexts. Research suggests this takes 50-70 repetitions before it begins to feel natural, which means roughly two weeks of consistent practice for most people.

Exercise Two: Exit Identification

Studies from emergency evacuation research reveal that people’s survival in crisis situations often depends on decisions made in the first 3-5 seconds. But those decisions require information that should have been gathered earlier, when there was time. In the famous 1977 Tenerife airport disaster, where two Boeing 747s collided on a runway, many survivors reported that they escaped through exits they’d noted during boarding, while others died trying to exit the way they’d entered despite smoke and fire blocking that path.

The exercise: every time you enter a new space—store, restaurant, office, building—immediately identify primary exit (door you entered), secondary exits (other doors), emergency exits (usually marked), and window exits if you’re on ground floor. Mentally plan: if something happened right now, which exit would you use? What obstacles lie between you and that exit?

This should take under five seconds once practiced. The research goal is building what psychologists call automaticity—the ability to execute a cognitive task with minimal conscious attention. Studies show this develops after approximately 100 repetitions, which means entering 100 spaces and consciously identifying exits. For most people, that’s about two weeks of normal daily activity if they practice consistently.

Exercise Three: Observation and Recall

Dr. Gary Klein interviewed expert decision-makers across domains—firefighters, intensive care nurses, military commanders—and found they rarely made decisions by weighing options consciously. Instead, they pattern-matched current situations to previous experiences and executed the first workable plan that came to mind. Klein called this recognition-primed decision making, and it only works if you’ve built a library of stored patterns.

The memory game builds this library. Sit in a public space for exactly three minutes. Actively observe everything—number of people, their appearances, what they’re doing, environmental details, sounds, lighting, anything unusual. Then leave and immediately write down everything you remember. Don’t take notes during observation—this trains recall, not transcription. Return to verify accuracy. Note what you missed.

Research suggests most untrained people recall perhaps 20-30% of observable details. After two weeks of practice, accuracy typically reaches 60-75%. The improvement comes not from better memory but from learning what to look for—training your attention spotlight to land on meaningful patterns rather than random details.

Exercise Four: Baseline Establishment

Dr. Paul Ekman, who studied deception detection for decades, found that most people are terrible at spotting lies because they look for nonexistent tells—body language cues, eye movements, speech patterns. What actually works is establishing baseline behavior first, then watching for deviations from that baseline. Someone who normally makes steady eye contact but suddenly stops isn’t displaying deception—they’re changing their pattern, which warrants attention to determine why.

The same principle applies to environmental awareness. When you enter a space, spend five minutes observing before engaging in your activity. What’s the typical noise level? How are people dressed? What are they doing? What’s the traffic pattern and flow? This establishes baseline. Then, throughout your time there, watch for baseline breaks—someone dressed inappropriately for the environment, behavior that doesn’t match others, unusual sounds or silence, people who focus on you or scan others rather than engaging in the location’s normal activities.

Research from the security industry shows that surveillance teams and predators typically break baseline in detectable ways—they’re focused on people rather than place, they’re dressed wrong for the context, they return repeatedly without obvious purpose, they position themselves for observation rather than participation. Training yourself to establish baseline first makes these breaks obvious rather than subtle.

Level Two: From Seeing to Understanding

In 1857, Louis Pasteur famously said that chance favors the prepared mind. He was talking about scientific discovery, but the principle applies to threat recognition. The prepared mind doesn’t see more data than the unprepared mind—it understands more of what it sees because it recognizes patterns that others miss.

Dr. Gavin de Becker, who spent decades studying violence prediction, argues that intuition about danger isn’t mystical—it’s rapid, unconscious pattern matching based on subtle cues your conscious mind hasn’t processed yet. The feeling that something’s wrong exists because your brain has detected a pattern break but hasn’t yet articulated what broke. Level Two training makes this pattern recognition faster and more accurate.

Pre-Attack Indicator Recognition

Research from correctional psychology and law enforcement training has identified behavioral patterns that often precede violent action. Dr. Richard Felson at Penn State, who analyzed thousands of violent incidents, found that attacks rarely come from nowhere—they follow predictable patterns if you know what to look for.

Target glancing behavior—where someone makes repeated brief glances at a specific person or their belongings—appears in approximately 70% of pre-assault observations. This isn’t casual looking. It’s assessment—determining location, awareness level, accessibility, potential resistance. Studies show predators often conduct this scanning process for 30-90 seconds before acting.

Hands concealment—keeping hands in pockets, behind back, or otherwise hidden—appears in 60% of weapon-involved assaults. The behavior makes sense: the predator is either concealing a weapon or preparing to deploy it. Research shows this cue becomes more reliable when combined with other indicators rather than appearing in isolation.

Interview behavior—approaching with questions or requests—appears in approximately 50% of stranger-initiated assaults. Dr. Jill Beech at the University of Portsmouth, who interviewed convicted offenders, found this served multiple purposes: it tests victim awareness and assertiveness, creates an approach justification that seems non-threatening, and positions the predator within striking distance.

The training challenge is learning to recognize these patterns without becoming hypervigilant. Most instances of these behaviors are innocent—someone glancing around a restaurant looking for friends, someone with cold hands in pockets, someone genuinely needing directions. The indicators become meaningful in combination or when they break baseline for the environment.

The OODA Loop

Colonel John Boyd, a military strategist and fighter pilot, developed what he called the OODA loop—Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. His insight was that combat isn’t won by the fastest or strongest combatant. It’s won by whoever completes their decision cycle faster. The person still observing while their opponent is already acting has lost before they realize the fight started.

Boyd’s framework applies directly to threat response. Observe the environment and detect the pattern break. Orient by placing it in context—is this normal for this location? Does it make sense given other factors? Decide on your action based on the assessment. Act immediately without second-guessing. Then loop back to Observe—has the situation changed based on your action?

Research from the Force Science Institute shows that trained responders complete OODA loops in 1.5-2 seconds, while untrained people take 4-6 seconds or freeze entirely trying to decide what to do. The difference isn’t physical speed—it’s having pre-made decisions that eliminate the Decide phase. If someone approaches testing my boundary, I will verbally set a boundary and create distance. No deliberation needed.

Body Language Interpretation

Dr. Amy Cuddy at Harvard studied how body language reflects internal state and, reciprocally, how changing body language changes internal state. Her research revealed that posture, breathing patterns, and muscle tension provide reliable indicators of someone’s threat level—not because they’re trying to signal threat, but because the autonomic nervous system prepares the body for action in predictable ways.

Hands visible and relaxed versus hidden or clenched. Shoulders level versus raised. Stance square versus bladed. Breathing normal versus rapid or controlled. Jaw relaxed versus clenched. These aren’t conscious choices—they’re physiological responses to stress and preparation for violence.

The training isn’t about reading minds. It’s about recognizing when someone’s physiology doesn’t match the social context. Someone with a bladed stance, raised shoulders, clenched fists, and controlled breathing at a coffee shop isn’t relaxed. Their body is preparing for action even if they’re not consciously planning violence. That pattern break warrants increased awareness and distance.

Level Three: Predicting What Happens Next

Chess grandmasters don’t see more moves than amateur players. They see different moves—specifically, they see the most likely next moves based on the current position and their opponent’s style. Research shows grandmasters evaluate perhaps 50-60 possible moves in a position, while amateurs might consider 200. The grandmaster eliminates unlikely options instantly based on pattern recognition, leaving cognitive resources to analyze the most probable scenarios deeply.

Level Three awareness works the same way. You’re not trying to predict every possible thing that might happen. You’re identifying the most likely next developments based on current patterns and positioning yourself accordingly.

Pattern Prediction Exercise

Dr. Gary Klein’s research on expert decision-making revealed that prediction accuracy increases dramatically with a specific training method: observe a situation, make an explicit prediction about the next 2-3 actions, watch to see if you’re correct, and analyze why you were right or wrong. The feedback loop is essential—prediction without verification doesn’t improve accuracy.

Practice in low-stakes situations. Watch someone approaching a door: will they pull or push? Hold it for the person behind them? Check their phone before entering? Watch someone in a grocery store aisle: will they compare prices, grab something quickly, or stand confused? Watch a car at an intersection: will they turn, go straight, or do something unpredictable?

Research suggests prediction accuracy improves from roughly 40% baseline to 70-80% after two weeks of daily practice. The improvement comes from learning what cues actually predict behavior versus what you think should predict behavior. Turns out people’s gaze direction 2-3 seconds before acting is a far better predictor than their body orientation or speed.

If-Then Scenario Planning

Psychologist Peter Gollwitzer at NYU has published extensive research on implementation intentions—plans that take the form “if situation X occurs, then I will perform action Y.” His studies consistently show that people with implementation intentions are 2-3 times more likely to follow through than those with only general intentions.

The mechanism relates to cognitive load under stress. Dr. Roy Baumeister’s work on ego depletion demonstrates that decision-making consumes cognitive resources, and those resources deplete under stress. During a threat, your cognitive capacity for deliberation plummets. Pre-made decisions bypass this limitation because they’re stored as simple stimulus-response patterns rather than problems requiring analysis.

The training: in every environment, identify 3-5 potential problems and create if-then plans. If fire breaks out, then I exit via the back door; if blocked, I use the front window. If someone follows me to my car, then I turn and confront them verbally at 20 feet while pulling out my pepper spray. If the person next to me on the train acts threateningly, then I move to a different car at the next stop or pull the emergency communication if the train is moving.

Research suggests these plans should be specific and actionable. “I’ll be careful” isn’t an implementation intention—it requires real-time deliberation about what “careful” means. “I’ll create 20 feet of distance and have my hand on my pepper spray” is executable immediately without deliberation.

Tactical Positioning

Military research on force protection reveals that positioning confers more survival advantage than combat skills in most scenarios. Dr. Tony Blauer, who has trained military and law enforcement for three decades, emphasizes that where you position yourself before a threat develops matters more than how well you can fight once the threat is immediate.

The principles: back protected when possible—you can’t defend what you can’t see. Face entrances—see threats approaching rather than being surprised from behind. Position near exits but don’t block them—you want escape options without trapping yourself. Maintain distance—the average attacker covers 21 feet in 1.5 seconds, so maintaining 20+ feet of buffer space gives you 1-2 seconds of reaction time. Use obstacles as barriers—position furniture, counters, or distance between yourself and potential concerns.

The training makes tactical positioning automatic. When choosing where to sit in a restaurant, evaluate: can I see the entrance? Is my back protected? Is there a clear path to exits? When standing in line, position slightly offset from the person behind you rather than directly in front—this eliminates the blind spot and makes approach from behind require more obvious movement.

Studies show that people who practice tactical positioning for 2-3 weeks report it becomes so automatic they feel uncomfortable in poor positions even when no obvious threat exists. That discomfort is useful—it’s your trained pattern recognition signaling that you’ve positioned yourself disadvantageously.

The Smartphone Problem

In 2012, researchers at Western Washington University conducted an experiment that’s become infamous in psychology. They had a clown on a unicycle ride through a plaza while observers counted the number of people walking past. The catch: about half the people walking through the plaza were talking on cell phones. Of the people not on phones, 75% noticed the unicycling clown. Of the people on phones, only 25% noticed it.

The researchers called this “inattentional blindness in plain sight”—the phone conversation consumed so much cognitive bandwidth that people became functionally blind to their environment, even to stimuli as unusual as a clown on a unicycle. And this was in 2012, before smartphones became truly ubiquitous.

Dr. David Strayer at the University of Utah, who studies distraction and attention, has documented that phone use doesn’t just reduce awareness—it eliminates it almost entirely. His eye-tracking studies show that people on phones look at their environment but don’t process what they’re seeing. Their eyes scan across pedestrians, vehicles, and obstacles, but the visual information never reaches conscious awareness because their cognitive resources are consumed by the conversation or screen interaction.

For situational awareness, this creates a paradox. The device that could summon help, record evidence, or light your path is the same device that makes you maximally vulnerable by destroying your threat detection capability. Research from the National Crime Victimization Survey confirms this isn’t theoretical—phone use appears as a factor in approximately 40% of urban street crimes, with offenders explicitly stating they selected victims who were distracted by phones.

The solution isn’t avoiding phones in public—that’s impractical for most people. The solution is implementing what cognitive psychologists call context-dependent usage rules that maintain baseline awareness:

Before checking your phone in public, stop moving. Studies show that walking while phone-distracted reduces awareness by approximately 90% compared to standing still while phone-distracted, which reduces awareness by about 70%. The difference relates to cognitive load—navigation plus phone interaction overwhelms attentional resources completely.

Position your back against a wall or solid surface before extended phone use. This eliminates the blind spot and forces potential threats to approach from a direction you’re more likely to notice peripherally.

Limit phone checks to 20-30 seconds. Research shows awareness degrades exponentially with time—a 20-second phone check allows you to maintain rough environmental awareness, while a 5-minute check leaves you completely unmoored from your surroundings and requiring 10-15 seconds to reorient after putting the phone away.

Complete a full environmental scan immediately after putting the phone away. Dr. Michael Posner’s research on attention switching shows that it takes 3-5 seconds to fully disengage from one task and reengage with another. During phone use, threats can close distance significantly. The post-phone scan recovers situational awareness before continuing movement.

Never use headphones while walking in public. While phone screens destroy visual awareness, headphones destroy auditory awareness—the car approaching from behind, the person calling out, the group’s conversation volume dropping as you approach. Research shows that auditory cues often provide earlier threat warning than visual cues because sound travels around obstacles that block line of sight.

What Success Actually Looks Like

Dr. Anders Ericsson spent his career studying expertise across domains—chess, music, athletics, medicine. One of his consistent findings: subjective assessment of skill is nearly worthless for measuring actual performance. People who think they’ve improved often haven’t, and people who feel they’re progressing slowly may actually be improving rapidly. The solution is objective measurement against specific benchmarks.

For situational awareness, success looks like this at different training stages:

After two weeks, you should be able to identify all exits in any space within 10 seconds of entering without conscious effort—it’s become an automatic scan. You should complete five-second environmental scans naturally throughout any public outing without timer reminders. You should recall at least 10 specific details from a 3-minute observation period with 60% accuracy. And you should catch yourself before extended phone use and implement positioning rules automatically.

After four weeks, you should establish environmental baseline within 5 minutes of arriving at any location. You should identify pre-attack indicators in real-time without referring to lists. You should complete OODA loops—observe, orient, decide, act—in under 3 seconds for common scenarios. And you should maintain Condition Yellow for entire public outings without it feeling effortful or exhausting.

After six weeks, you should predict behavior with 60-70% accuracy based on observable cues. You should have instant if-then response plans for common scenarios in familiar environments. You should automatically choose tactical positioning when selecting seats or standing locations. And you should maintain awareness even when cognitively distracted by conversations or tasks.

After eight weeks, 360-degree awareness should be automatic—you’re tracking people and events in front, beside, and behind you without conscious scanning. You should use reflective surfaces naturally to monitor blind spots. You should score 80% or higher on comprehensive awareness assessments. And other people should begin commenting on how aware or alert you seem.

Research from skill acquisition studies suggests that subjective experience lags objective improvement. The exercises will feel awkward and require conscious effort for 3-4 weeks even as your performance metrics improve. Then, suddenly, they feel natural. This is the automation threshold—when practiced skills move from conscious execution to background processing.

The key indicator of genuine progress: you begin feeling uncomfortable or even slightly anxious in situations where you can’t maintain awareness—crowded spaces where you’re pressed against others, environments with poor visibility, situations where you’re prevented from tactical positioning. This discomfort isn’t paranoia. It’s your trained pattern recognition system signaling that something important (your awareness capacity) has been compromised.

Why Awareness Skills Degrade

Dr. Hermann Ebbinghaus discovered the forgetting curve in 1885—his research showed that learned information degrades predictably over time without reinforcement. More recent work by Dr. Henry Roediger at Washington University demonstrates that skills degrade even faster than factual knowledge, and physical skills degrade faster than cognitive skills. But here’s the interesting part: awareness skills fall into a category that degrades fastest of all—what researchers call vigilance tasks.

A study from the U.S. Army Research Institute tracked soldiers’ threat detection accuracy after combat deployment. During deployment, with daily practice and genuine stakes, detection rates hovered around 85-90%. Six months after returning home without practice, detection rates dropped to 45-50%—barely above untrained baseline. Twelve months later, they were statistically indistinguishable from civilians who’d never received training.

The mechanism relates to what psychologists call the cost-benefit calculus of attention. Your brain allocates cognitive resources based on perceived utility. In high-threat environments, awareness delivers obvious benefit—it prevents actual dangers—so your brain prioritizes it. In low-threat environments, awareness seems to deliver no benefit because nothing bad happens, so your brain deprioritizes it to conserve resources for other tasks.

This creates a paradox: the safer your environment, the faster your awareness skills degrade. And awareness skills degraded means you won’t detect the rare threat when it does emerge, which means you’re least prepared precisely when preparation matters most.

The solution isn’t maintaining combat-level vigilance constantly—that’s exhausting and counterproductive. The solution is structured maintenance that preserves skills without consuming excessive cognitive resources:

Daily maintenance takes approximately 5 minutes. Practice awareness during one routine activity—your commute, grocery shopping, walking the dog. Complete five-second scans throughout the activity. Identify exits wherever you go. Maintain these basics and the underlying skill set remains accessible.

Weekly maintenance takes 15 minutes. Conduct one focused observation session in a public space—practice establishing baseline, identifying pattern breaks, making behavioral predictions. Practice one specific skill from the training modules. Review and refine your if-then scenario plans for common environments.

Monthly maintenance takes 30 minutes. Complete a full-spectrum assessment test—spend 10 minutes in a moderately crowded public space, then document everything you observed and verify accuracy. This reveals which skills have degraded and need additional practice. Update your training based on any new environments you’re frequenting or new threat patterns you’ve learned about.

Research from skill retention studies suggests this maintenance schedule preserves approximately 80-90% of trained capability indefinitely. The 10-20% performance decrease from peak trained state is acceptable because peak state required intensive daily practice that’s unsustainable long-term. The goal isn’t maintaining absolute peak performance forever. The goal is maintaining functional capability that’s dramatically superior to untrained baseline.

Building Your Training System

Dr. Charles Duhigg, who studied habit formation and organizational behavior, argues that the difference between people who sustain behavioral changes and those who don’t isn’t motivation or willpower—it’s system design. People who succeed build systems that make the desired behavior easier than the default behavior. People who fail rely on remembering to do things differently, and memory under pressure is unreliable.

For situational awareness training, this means creating environmental cues and structural supports that make practice automatic rather than something you have to remember:

Week one focuses on establishing the five-second scan and exit identification as automatic habits. Set your phone timer to vibrate every 5 minutes during designated practice periods—30 minutes daily for the first three days at home, then 30 minutes daily in public spaces for days four through seven. The goal is 50-70 repetitions of the behavior, which research suggests is sufficient to establish initial automaticity.

Week two adds the observation and recall exercise and baseline establishment. These exercises don’t require timers—they’re event-based habits triggered by entering new spaces. The cue is the door—every time you enter somewhere, spend the first 3-5 minutes observing and establishing what’s normal before engaging in your primary activity. Practice 3-4 times throughout the week, documenting accuracy each time.

Weeks three and four shift to comprehension training. Study the pre-attack indicators until you can recall them without reference. In public spaces, actively watch for these specific patterns. Keep a small notebook or phone note documenting observations—who displayed which indicators, what the context was, what the outcome was. The goal is training your visual system to catch these patterns automatically rather than requiring conscious searching.

Weeks five and six focus on projection skills. Practice behavioral prediction continuously in public spaces—make explicit predictions, observe outcomes, analyze accuracy. Create if-then scenario plans for every new environment you enter. Practice tactical positioning every time you choose where to sit or stand. The goal is making these assessments so rapid they feel instantaneous.

Weeks seven and eight integrate all skills into seamless environmental processing. You should be scanning, establishing baseline, identifying patterns, making predictions, and positioning yourself tactically without conscious effort. The exercises become your default mode of operating in public rather than special activities you practice.

Research from expertise development suggests this 8-week intensive training period establishes foundational skills that can be maintained with significantly less time investment. But the initial intensive period is essential—trying to build awareness gradually through casual practice takes 6-12 months to achieve the same results because the skills don’t reach automaticity before degrading.

The key to system design: make awareness practice piggyback on existing routines rather than adding new time commitments. Practice during your commute, during grocery shopping, during lunch breaks. Use waiting time—in lines, in waiting rooms, before meetings—for observation exercises. Build awareness into activities you’re doing anyway rather than trying to add new dedicated practice time to an already full schedule.

The Trainable Nature of Awareness

Daniel Simons’s invisible gorilla experiment revealed something troubling about human attention—we miss obvious things constantly, and we’re not even aware we’re missing them. But his follow-up research revealed something more hopeful: attention is plastic. It can be trained. People who practice systematic scanning, who build pattern libraries through repeated observation, who learn to recognize baseline breaks—these people see the gorilla.

More importantly, they see the things that matter for safety. The person conducting pre-attack assessment. The situation developing wrong. The opportunity to avoid confrontation before it begins. Research consistently demonstrates that awareness prevents threats not by enabling you to fight better but by removing you from the target pool entirely.

Criminals select victims based on observable inattention. Display attention, maintain environmental scanning, position yourself tactically, and you’ve eliminated 90% of opportunistic crime risk. Not because you’ve become intimidating or dangerous, but because you’ve made yourself unprofitable as a target compared to the abundant supply of unaware alternatives.

The training methodology presented here isn’t theoretical. It’s built on decades of research from cognitive psychology, military science, criminal behavior analysis, and expertise development. The exercises work because they target the specific cognitive systems that enable awareness—attention allocation, pattern recognition, behavioral prediction, and automated decision-making under pressure.

The eight-week intensive training period establishes the foundation. The maintenance schedule preserves it indefinitely. And the system design ensures practice integrates into daily life rather than requiring unsustainable time commitments or motivation.

Situational awareness isn’t a mystical sixth sense possessed by special operators and denied to civilians. It’s a trainable cognitive skill built through systematic practice. Start with the five-second scan. Add exit identification. Layer in observation and recall. Build comprehension through pattern recognition. Develop projection through behavioral prediction.

In two months, you’ll have cognitive capabilities that most people never develop. You’ll see what others miss. You’ll recognize patterns that others overlook. You’ll have time to respond while others are still processing what happened.

And that might be the difference between being selected as a target and being passed over. Between freezing in surprise and responding decisively. Between becoming a victim and remaining safe.

The gorilla walks through the frame constantly. Most people never see it. But you can train yourself to see it every time. Start today.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to develop effective situational awareness?

Research from cognitive psychology shows measurable improvement in 6-8 weeks of structured practice. Studies by Dr. Daniel Simons at the University of Illinois demonstrate that attention is trainable—subjects who practiced environmental scanning exercises showed 60-70% improvement in threat detection within two months. However, like any cognitive skill, maintenance requires ongoing practice. Most people see significant changes in their baseline awareness within the first two weeks of consistent training.

Is situational awareness the same as paranoia?

They’re neurologically opposite states. Paranoia involves elevated stress hormones, hypervigilance without productive focus, and threat perception without accurate assessment. Situational awareness, according to research from the U.S. Army Research Institute, is characterized by calm alertness, accurate environmental scanning, and appropriate threat calibration. Dr. Mica Endsley’s work on situation awareness shows it operates in what she calls relaxed readiness—maintaining broad attention without anxiety. If awareness practice increases your stress rather than your confidence, you’re training incorrectly.

Can situational awareness really prevent attacks?

Studies by Dr. Betty Grayson at Hofstra University demonstrate that criminals systematically select victims based on observable awareness cues. When she showed footage of pedestrians to convicted offenders, they consistently identified the same individuals as targets—those displaying distraction and poor environmental scanning. Research from the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that environmental awareness eliminates approximately 90% of potential criminal opportunities, not by enabling you to fight off attackers, but by removing you from their selection pool entirely. Criminals overwhelmingly prefer unaware, predictable targets.

Do I need military or law enforcement training to develop situational awareness?

Research suggests civilian training may actually be more effective for civilian contexts. Dr. Gary Klein’s work on naturalistic decision-making shows that expertise is domain-specific—military awareness skills optimize for combat scenarios with different threat patterns than civilian environments. Studies from the Force Science Institute demonstrate that civilians can develop highly effective awareness through simple, targeted exercises focused on pattern recognition, baseline establishment, and environmental scanning. The key is consistent practice, not formal credentials.

What’s the difference between situational awareness and just paying attention?

Dr. Mica Endsley’s three-level model of situation awareness distinguishes between simple perception and genuine awareness. Paying attention (Level 1) means noticing details—how many people are present, where exits are located. Situational awareness adds comprehension (Level 2)—understanding what those details mean, whether behavior is normal for the context. The highest level, projection (Level 3), involves predicting what happens next based on current patterns. Research shows most people operate only at Level 1, and weakly. True situational awareness integrates all three levels into automatic cognitive processing.

How do I practice situational awareness without looking paranoid or suspicious?

Eye-tracking research from Dr. Richard Nisbett at the University of Michigan shows that effective environmental scanning appears completely natural to observers—it mimics the broad contextual attention patterns found in many non-Western cultures. The key is fluid, casual scanning rather than fixed staring. Practice the five-second sweep: brief, natural glances that cover your environment without lingering on individuals. Studies show this pattern appears as ordinary curiosity rather than surveillance behavior. The goal is maintaining peripheral awareness through movement and casual observation, not intense scrutiny that draws attention.

Does situational awareness work in familiar environments, or only in dangerous areas?

Crime statistics from the Bureau of Justice reveal that most violent victimizations occur in familiar locations—home neighborhoods, regular commute routes, frequently visited businesses. Familiarity creates what researchers call recognition complacency, where your brain assumes nothing has changed and stops actively scanning. Studies show that criminal predators specifically exploit this complacency, timing attacks in familiar locations where victims feel safe and let their guard down. Effective awareness training emphasizes maintaining scanning habits regardless of environmental familiarity.

What if I’m naturally unobservant—can I still learn these skills?

Neuroplasticity research demonstrates that observation ability is remarkably trainable at any age. Dr. Daniel Simons’s studies on inattentional blindness show that people who initially miss obvious environmental details improve dramatically with targeted practice—in some cases showing 300% improvement in detection rates after structured training. The brain’s attentional networks physically change with practice, creating new neural pathways that make environmental scanning increasingly automatic. Natural aptitude provides minimal advantage over trained skill—what matters is consistent, deliberate practice.

How do I maintain situational awareness while using my phone in public?

Research from the University of Western Australia shows that phone use creates inattentional blindness—users literally don’t see unexpected events in their environment, even dramatic ones. The solution isn’t avoiding phones entirely but implementing what cognitive psychologists call attentional rules: stop moving before checking your phone, position your back against a wall or solid surface, limit phone checks to 20-30 seconds, complete a full environmental scan immediately after putting the phone away. Studies show brief phone checks with these protocols maintain approximately 70% of baseline awareness, versus near-zero awareness with unrestricted phone use.

What’s the biggest mistake people make when trying to improve situational awareness?

Cognitive load research identifies information overload as the primary training failure. People attempt to notice everything simultaneously, which paradoxically decreases awareness by overwhelming attentional resources. Studies from the U.S. Army Research Institute show that effective training follows hierarchical skill building—master one observational element before adding another. Begin with simple exit identification, add crowd estimation, then layer in behavioral assessment and threat evaluation. Dr. Gary Klein’s expertise research demonstrates that skills become automatic through focused practice on individual components, not by attempting comprehensive awareness immediately.

Tools That Support Your Awareness

Awareness identifies threats early. But when awareness alone isn’t enough, you need reliable defensive tools ready to deploy. Browse our selection of research-backed self-defense products at Revere Security—pepper spray formulated to NIJ specifications, stun devices with verified electrical output, personal alarms exceeding 120 decibels, and tactical flashlights designed for disorientation and escape.

Because awareness tells you when to act. Your tools provide the means to act decisively.